Detroit: Become Human is Quantic Dream’s fourth ‘interactive film’, following Fahrenheit, Heavy Rain and Beyond: Two Souls. All have been extremely ambitious projects, each one building on the last in getting closer to replicating the look, feel and emotion of a real movie. Their success, however, can be debated and I’ve made no secret of my feelings on those games shortcomings in my previous reviews. Exclusive to PS4, Detroit: Become Human feels like director David Cage has taken a step back and looked at his work as a whole, taking what worked, eschewing some of what didn’t work, and remixing elements into a new experience. That said, it is still a David Cage game, so you know. Be prepared for a wild ride.

Detroit: Become Human joins a pretty crowded genre of science fiction which asks the age-old question – what happens when humanity creates robots? And what happens when they become self aware? Detroit takes place, where else, in Detroit in the year 2038, where androids have become as ubiquitous as household appliances, and treated in much the same way. Sold in shiny Apple Store-like showrooms for reasonable prices, androids are used by families, governments and businesses, essentially as a slave race. But, things are starting to change as more and more androids seem to go ‘deviant’ and rebel against their programming, displaying real emotions, which if left unchecked could lead to a revolution.

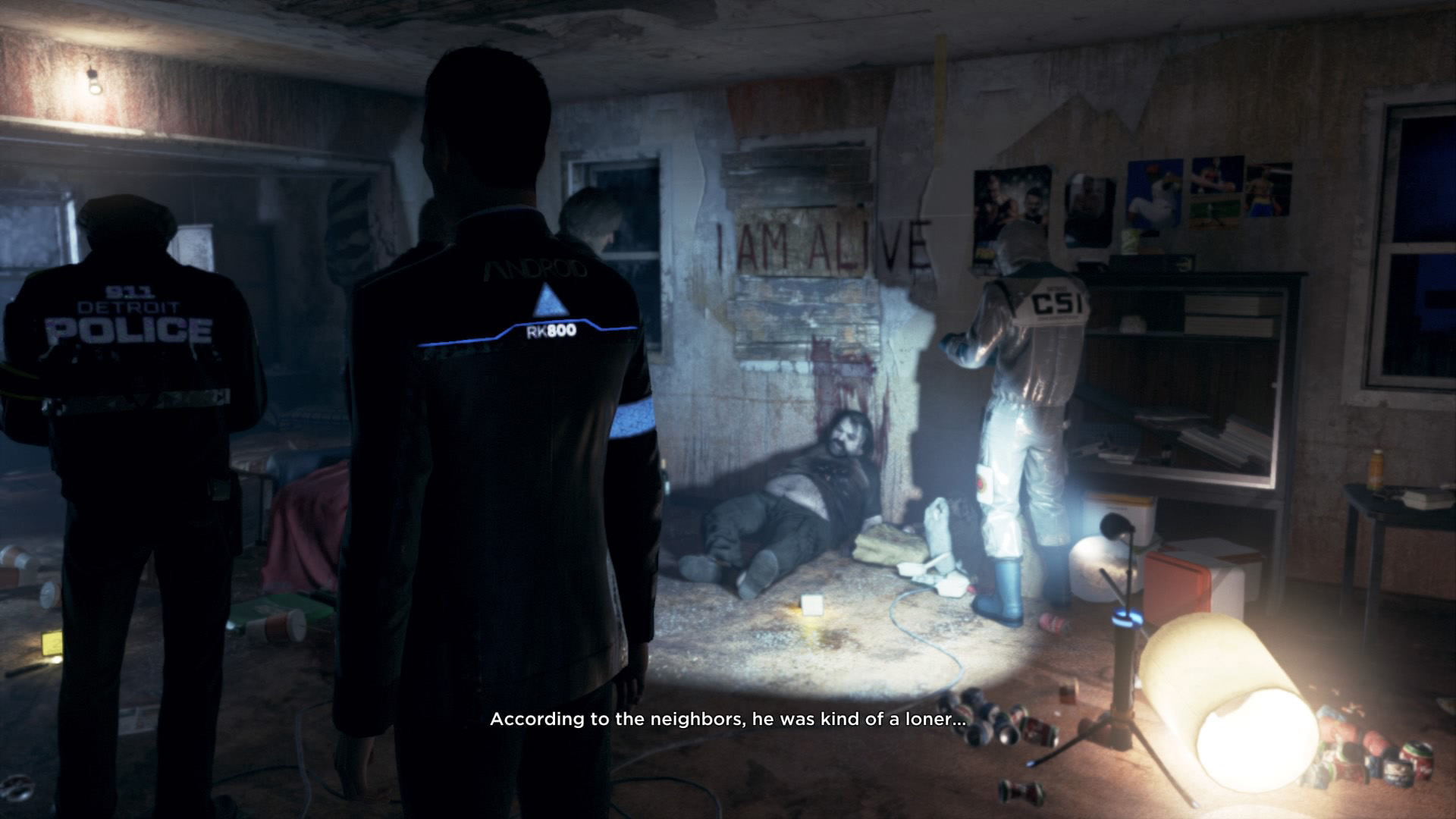

We see this world through the eyes of three androids: Kara, a domestic model bought by the abusive father of a withdrawn little girl; Connor, a prototype detective android on a mission to uncover the trigger behind android ‘deviancy’; and Markus, the caretaker of an elderly artist who may also control the destiny of the entire android race. Through them we see that humanity has learned nothing from the past, treating androids terribly with contempt and blatant racism, despite the fact that androids appear and act entirely human themselves – aside from a small LED indicator on their temple.

Detroit is a game that relies almost entirely on its narrative, and if you have any experience with sci-fi at all, then you’ll know the subject matter has been dealt with thoroughly before. From Battlestar Galactica to Westworld screening on TV now, to Spielberg’s A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, to even that Will Smith magnum opus, I, Robot. You’ll see ideas and even scenes drawn from all of these and more, as Detroit frequently seems to run into inevitable cliches – from a robot uprising and demand for civil rights, to a robot partnered with a robot-hating detective (no matter how ably he is played by Clancy Brown). All fiction is built upon the work of others, but Detroit frequently seems like a reshuffling of old ideas – including a story beat from Toy Story, strangely enough. Unfortunately, Detroit doesn’t take the opportunity to dive into the nature of artificial consciousness as much as those other works – indeed, consciousness is later treated as simple to achieve as flicking a switch in the narrative.

That said, the execution of these ideas ranges from adequate to outstanding. Of the three narratives, Kara’s protection of the little girl, Alice, and their journey together hits the hardest emotionally. It resonates as an analogy for a mother and child looking to escape a horrific home situation, and the bond that forms between the two is both sweet and believable. As with many AAA-games, real actors’ performances were captured and translated onto highly detailed digital models that impressively recreate every small emotion and reaction. The work of these performers is allowed to shine through thanks to the impressive visuals.

The point of difference in this man-vs-machine tale is in its David Cage-ness. That je ne sais quoi, which essentially translates to the blunt and highly dramatic way events unfold. The game plays out in a series of individual scenes divided between the three leads, with control swapping to the next one at the end of a chapter, much like Heavy Rain. As a scene begins, if you were to imagine the absolute most dramatic thing that could possibly happen, nine times out of ten you’d be right. Situations are regularly taken to the extreme, and in the process subtlety is lost. Detroit uses imagery from real life moments in civil rights and oppression. These range from groan-inducingly blatant and obvious – androids are forced to travel in the back of the bus (do you get it?) – to astonishingly confronting. Without delving too much into spoiler-territory, there is explicit and extreme holocaust imagery featured that could very well have steered too far into tasteless, if the narrative didn’t take the scenes so deadly seriously.

However, Detroit can also actually be fairly clever in its vision of a future run by androids. An early, almost comical moment, sees Markus sent to a shop to purchase and pick up paints for his owner – from a robot shopkeep, in a transaction that involves no humans, and one you would think would have been much more easily dealt with online. Android ‘parking bays’ line the streets of Detroit, which are essentially just small areas of cover where humans can leave their androids while they shop. There’s a wealth of world-building that David Cage is content to leave in the background, informing the events of the story, rather than headfirst careening into them, as in some of his past games – and that’s a good thing. There are still logical inconsistencies and some strange moments, not the least of which is a ‘twist’ which comes from nowhere and ultimately doesn’t matter.

Your actual impact as a player is similar to other games like Beyond and Heavy Rain. In scenes, you can control your character to find clues and information that will affect their choices later on, as cinematic dialogue and action sequences present options for you to progress the story. Frequently these are moral choices, and your decisions affect your relationship with other characters, both in how they see you and their eventual fate. Actual gameplay is limited to a series of QTE actions, where you follow on-screen prompts that more-or-less represent the action you need to take (the most jarring of these being the ones requiring motion control, which sometimes fails to register).

From the very first trailer, Detroit touted its ‘flowchart’ system, where your decisions can lead to wildly different outcomes. The best example of this control comes in the first scene of the game. Connor, arrives at a police-filled skyscraper penthouse to negotiate a hostage rescue from a deviant android. The clues he’s able to find scattered around the apartment affect his options when talking down, meaning that the keen and observant have a better chance at rescuing the hostage – although with a ticking clock in the background, you don’t have unlimited time. It’s a tense, well-executed scene, that succeeds in forcing you to make hard choices under pressure.

And to Detroit‘s credit, there are a quite a few more scenes like it in the game, but not enough to feel like you have total agency over this choose-your-own-adventure story. Your control over events varies, as many scenes still follow a linear course of action that needs to get its characters to the next. I played through Detroit twice, with the first sticking to my honest gut feelings and decisions, and the second trying to diverge as much as possible from my original playthrough. While there are some major differences, they largely don’t appear until the end of the game, where characters have their own unique scenes and situations depending on where your choices have led them. This made my replay a little tiresome, as large swathes of the story don’t change between playthroughs, and there’s no way to fast forward through already-watched scenes.

That said, there is a checkpoint mechanic available from the game’s main menu that allows you to reload from a key decision point in the flowchart and continue on. It’s an appreciated feature, although there aren’t quite enough of them to save having to replay through some lengthy scenes again and again, if you’re interested in seeing all the available outcomes. Filling in the flowchart with all possible actions is encouraged by the game, and rewarded through points you can spend on behind-the-scenes extra material.

Despite a lack of originality, Detroit: Become Human finds a way to work in a lot of small ways. Small emotions on the performers’ faces, thanks to the great tech, leave a big impact in dramatic scenes. Music cues, which seem individual and unique between the three main androids, go a long way to heightening the heroism or tension of a scene. Even Detroit‘s main menu is kind of clever, featuring your own personal android who’ll monitor your progress, comment on your interior decorating, and ask you confronting questions about the relationship between humans and AI. Most importantly for a David Cage game, Detroit: Become Human never goes completely off the rails. Events do escalate, and there are big moments, but Cage seems to have gained the ability to ground the narrative for the most part, which goes a long way to making this his most successful story yet. The story is familiar, but there is a strange humanity about the whole affair, much like Detroit‘s androids, that make it an intriguing delve into the future.

-Largely terrific performances, and tech that captures those performances -Builds an interesting, believable future world -Ability to re-play decision points and jump around is appreciated -Some arresting imagery and moments

-Prone to cliche, bombast and a lack of subtlety -Occasionally inconsistent logic -While the story does diverge in some key ways towards the end, much more remains the same through multiple playthroughs