Though it should be obvious by now; disregard any and all preconceptions associated with the franchise labelling of Prey. Arkane’s work is so far removed from literally everything associated with Human Head Studios that this Prey doesn’t even constitute as a reboot. Prey in name only, Arkane’s science fiction horror is no lesser its own fresh narrative context than Dishonored was to Thief, and is best experienced with a clear perspective free of bias, allowing the brooding tension and horror of erratic alien organisms to infest every corner of the mind.

Prey takes place in a futuristic, yet familiar world. In short, Kennedy lived and the space race evolved, climaxing with the establishment of the Talos I space station, a futurist home to neuroscientific advancement and technological wonder, alongside the study of the Thyphon alien species. Of course, this is integral to both the aforementioned scientific discoveries and as the narrative catalyst of inevitable disaster required to set the precedent for vent crawling, turret hacking, and alien slaughter. In space no-one can hear you sagely advise that experimenting on misunderstood extraterrestrials is a tremendously poor idea with predictably catastrophic results.

You are Morgan Yu, a fragment of an identity with intentions and context that unravel throughout Prey‘s engaging psychological thriller story. Discoveries are drip fed through in-engine scripted events and environmental storytelling, narrative arcs developed through email chains, post-it notes, voice recordings, and clever visual cues that convey a convincing sense of presence and identity to the denizens of Talos I and the nightmare they’ve found themselves in. Prey rewards patience and investment in Arkane’s world building, appreciating time spent piecing together the interwoven narrative pieces and nuanced details that believably exist because they should and not because they have to.

This cornerstone of agency goes beyond expression of narrative to enrich Prey by design. Progression through Talos I is hindered only by keypass gateways and ability or gear bottlenecking, otherwise inviting an application of game systems limited only by expression of creative and critical thinking. Complexity of the role-playing ability trees and inventory management are not devalued, instead inviting minimalist hand-holding and objective pacing. Prey’s breadth of options in play are rarely overbearing or intrusive, almost sandbox-like in choice of upgrades and gear and application towards reaching objectives and self-delegated order. This should not be misunderstood as absolute freedom and world openness, instead the game provides a concise presentation of rules and guidelines for a consistent internal logic and offering freedom within this scope.

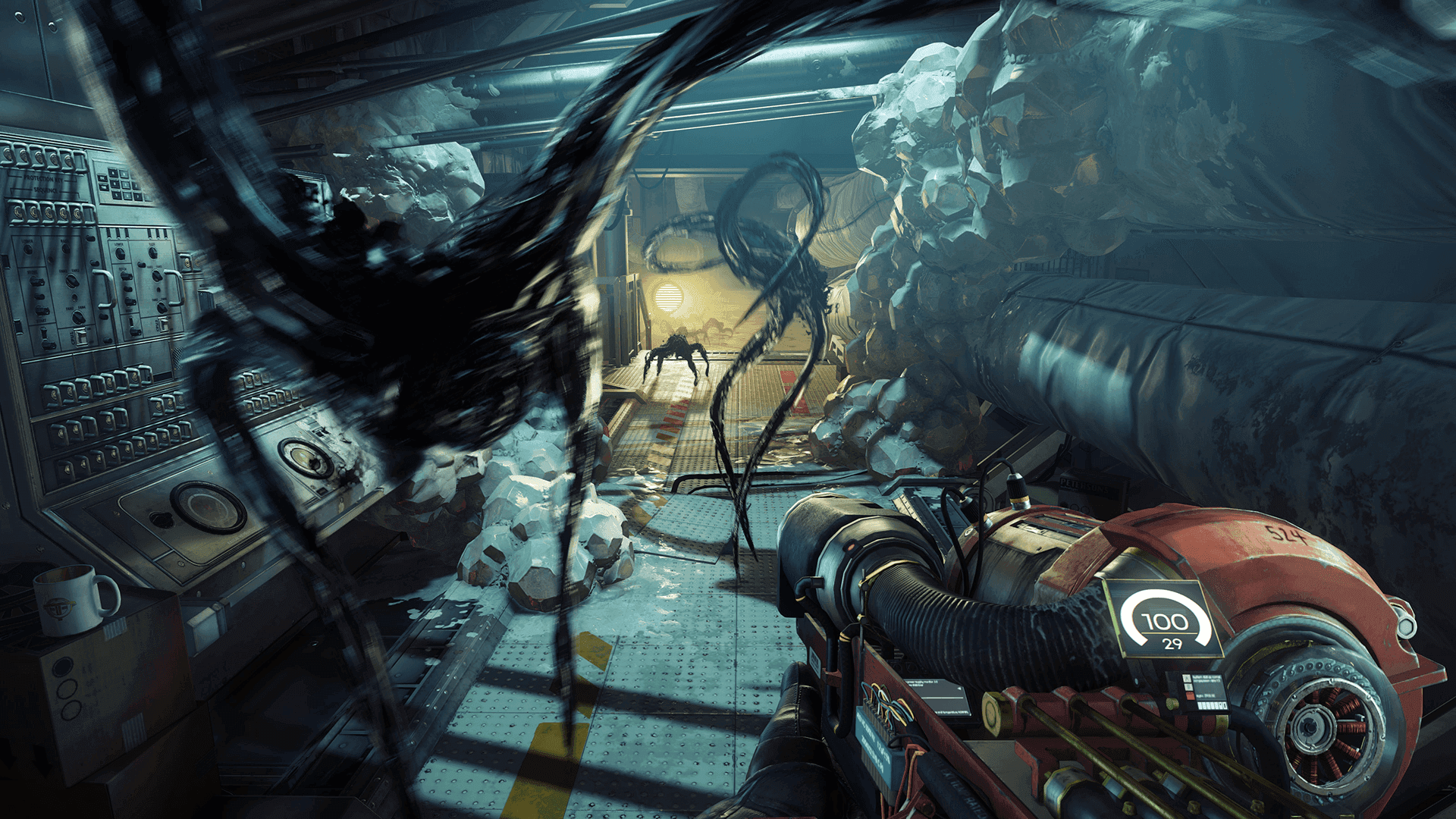

Awareness and agency of play balances between expressions of interaction with the game world and adaptation to the game world’s inflictions, namely survivalism requiring careful resource management, particularly of ammunition and first aid gear. Prey’s survival horror peaks come from synchronicity between these states, the tension in carefully analysing foyers and rooms to identify chameleonic Typhons masquerading as assorted office equipment while desperately scavenging gear necessary for self preservation, all the while attempting subconscious preparation for more complex challenges to come in hopes of reducing the window of unpredictability and failure. As an unbroken gameplay loop rarely if ever disrupted by cutscenes or rigid scripting stripping away interactivity, the immersion factor of moment-to-moment play is significant and highly rewarding.

Prey is a curious amalgamation of design philosophies attributed to not just Arkane’s own iconic work but also to the adhoc labelled “immersion sim” as a whole, leveraging learned game systems and structure from modernised RPGs like Dishonored 2 and Deus Ex: Mankind Divided. This is notably present in the acquirable skills, world interactivity, and options of play, while also derivative of the likes of System Shock and other mid-late 90s titles. Name dropping System Shock is paramount, as Prey fills a void left by the science fiction horror immersion sim that has been largely neglected since.

At a quick glance Prey can be forgivingly linked to BioShock, but noting this point of reference is important due to relevance to the aforementioned. Rewind to 2007’s launch of Ken Levine’s blockbuster and the significance of the latter, then marketed as a spiritual successor to System Shock 2, becomes apparent. Not to decry BioShock’s legacy or acclaim, but there’s no controversy in noting that the reception from an audience anticipating close parallels to System Shock 2 was that of disappointment. BioShock‘s commitment to game system streamlining and linearity forged a new beast, and humorously all these years later it’s Prey that so intimately resonates with Looking Glass Studios’ magnum opus. For all intents and purposes Prey is System Shock 3, a statement made with fully intended implicated praise.

Though intelligently elevating game systems to modern expectations and refinements, such as the clear and intuitive user interface despite the scope of game systems and world interactivity, Prey’s immersion sim family tree retains legacy holdovers through what is commonly described as 90’s jank. Derogatory and vague as the phrase so often is, this abstraction manifests in Prey through combat that never feels as tight and snappy in control and hit detection as other games (including Arkane’s own Dishonored), and a subjective repetitiveness to the game’s pacing and structure that runs the risk of wearing thin before the experience concludes. Both of these production facets occasionally work as an unusual strength: combat never so clumsy as to legitimately deteriorate encounters and instead sometimes accentuate the otherworldly alienness of the Typhon, and repetitive structure lending to an unbroken organic flow to exploration and the experience of play entire.

Though knowingly without the privilege of peeking behind the development curtain, armchair speculation alongside franchise context hints at a production that saw many iterations under a spectrum of visions, as Prey scrambled for focus and identity. Parroting the cliche “a few more months in the oven…” could very well be applicable here, if the objective was to elevate Prey’s production quality a notch higher, but it’s the observation of genre and franchise parallels to perhaps ensure risk free and deadline tight production scope that skewers with a double edged sword. Prey’s conceptual amalgamation is like a “Best of” album, the overwhelming familiarity of a vast array of game systems deserving of praise in their own right but never truly encroaching on blinding surprise or originality. To use Arkane as a point of reference, while Dishonored drew heavily from Thief as source material, Arkane’s work effortlessly elevated a wholly unique vision from the template design. Whereas Prey’s originality comes more from scattered moments of nuanced unexpected ticks within the framework of reasonable, familiar, and maybe even predictable design.

It’s thankful then that the chosen source material is so valuable that even at its worst Prey radiates with confidence in its otherwise safe vision. And when at its finest Prey is evocative of an enthralling science fiction horror immersion sim, one that has slumbered in the darkness of space since 1999, whose unexpected return is welcome with open arms.

Immensely agency driven in scope and play, backed by a decent psychological science fiction mystery laden with horror and tension.

Lost sparks of originality prevent the experience from elevating beyond a genre missing link.