Welcome to Obscure Retroness, a new feature at Rocket Chainsaw that we hope to make a regular. Our aim here is to spotlight games from eras past that may be just a little bit obscure and tough to track down and play in their original forms. To that end, any game that has the good fortune of making it onto this feature must fall under the following criteria:

-First and most obviously, a game shouldn’t be still in print and of this generation

-The game hasn’t been remade/re-released on another console to death

-A game should also be one that was actually released in western territories, so it’s not completely unattainable or unplayable even though it may now be extremely difficult

-Any game featured doesn’t necessarily have to be a good one – it could be quite a shocker and a writeup on it could be lots of fun

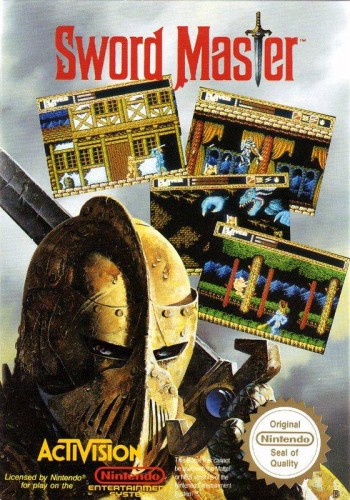

With that little intro out of the way, it’s time to start shining a light on the first game to be included in O.R, Sword Master!

First released by Activision in 1990 (or 1992, depending on which hemisphere you resided in), Sword Master comes from those early days of the NES, where most games had to have the word ‘Mario’ in the title to be a success on the console. Sword Master does not buck this trend too much, though it does follow the Mario series in some important ways. Your aim is to rescue a princess. From a castle. From something looking vaguely reptilian, with protrusions that serve no obviously discernible purpose – unless they’re some sort of euphemism, which may explain the princess-pilfering. To that end, you take up the mantle of a nameless warrior – or a Sword Master, if you will. And, in the most unsurprising development of all time, your main weapon is a sword. But it’s not the only thing that you can use to keep the minions of the reptilian god Vishok at bay on your mission to save the fair maiden of the land.

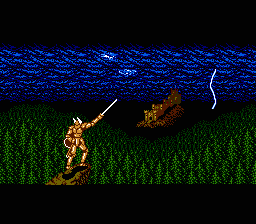

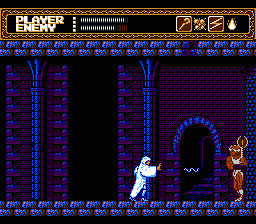

Your shield is perhaps your most important weapon of all in Sword Master – and it’s not even a weapon! What makes Sword Master just that little bit different for other sword-and-sorcery games of the time is how legitimately useful it can be in different ways, and how much strategy can be involved in its use. If you simply stand there and hold back, you can block many oncoming attacks from the front, but you can also crouch to block low and raise your shield to block high. That’s a whole three different frames of animation for a single function right there, almost unheard of in those early days of Nintendo gaming. But the combative shenanigans don’t quite end there. With the press of a button, your nameless warrior will don a cloak and become a magician, foregoing your sword and shield but gaining the power to use magical powers, like fireballs and thunderbolts. As it turns out, however, you won’t really use your magical powers that often and you can even forego collecting the magical pickups dropped by vanquished foes.

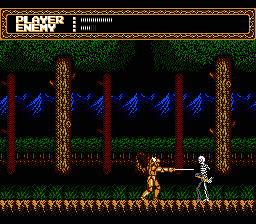

And those foes are quite an interestingly medieval bunch indeed. There’s the usual assortment of bats, rats and little scurrying things, but occasionally you’ll get locked into a mini boss battle, where your progress will be halted until you eliminate your enemy. The first of these is a skeleton who has a sword that both skewers you and shields them. It’s like fighting a doppelganger of yourself – minus the flesh, organs, armour and ability to go mage-ish. There’s an assortment of other characters of the usual medieval fare which act as proper bosses and recurring combatants, such as dragons, wizards, other knights and demons. Perhaps the most unique of all, however, are the orbs. Those floating, soulless orbs. They are, quite simply, indestructible and will not stop. The eyes only move in a simple up-down pattern most of the time, but this means that they’re in your way all the time right above treacherous crevasses. The only way to make the orbs move is a well-placed smack of the sword, but they will not be kept at bay for long. Those orbs always return to their former spots, in a slow but menacing way. In some ways those plain-but-indestructible orbs are almost as much of a pain to encounter as the final boss – none other than the lizardly one himself (itself?) – Vishok. Taking up most off the screen and coming from an era of simple but brutal bosses, Vishok surprisingly doesn’t use much in the way of physical attacks. Instead, the sinister saurian prefers to instead unleash what look like flying bricks, lightning and fireballs that bizarrely come from his gigantic hangnail.

Vishok and indeed the rest of the game are rendered in sublime detail. The animations, as mentioned previously, are of more frames than most games of that era. Your hero’s armour and movements are resplendent in all of their glory, and each piece of armour is distinct from the other. The level of detail here certainly shows how far the console had come in just five years, compared with the blocky visage of that original NES princess rescuer Mario. As impressive as the character sprites are, however, it’s the backgrounds of Sword Master that truly stand out as perhaps the most unique and memorable aspect of the game. Engaging in parralax scrolling, there are up to three different background plates onscreen at once, giving the areas of your travels a real sense of depth and openness. That other ever-important presentation, the audio effects, are not quite as significant or impressive, but are still streets ahead of much of Sword Master’s contemporaries. Each boss character has its own unique guttural cries in the midst of battle, though admittedly they make the same moan upon defeat. The music, on the other hand, is a glorious collection of 8-bit tracks, and you never once get the feeling that a track has been recycled. Married with the backgrounds, the music goes some way to setting a different feel for each level, from the introductory forest proceedings to the battle with Vishok at the very end.

And so we draw to the conclusion of our look back at playing Sword Master. As for tracking it down today, it’s a feat that isn’t quite as arduous as trouncing those immovable orbs of doom. Many cartridge-only copies can be found for around $16-$25 in this part of the world, though completed copies can fetch around $40 across the globe. It may not be quite worth that much for its gameplay value alone. However, if you’re curious about looking at it from a technical perspective then it represents something unique to its era and worth looking at if you know someone with a copy.

While you all go and decide to sift through my belongings for my own cartridge of Sword Master, it’s time to close out this very first edition of Obscure Retroness. If you’ve got a game that you think should be spotlighted for our next edition, type it away in the comments below – it may just wind up featured on here! Which game will make it into the next installment? Who will take a look at it? Click away next time to find out!